Foreword

Architectural plans, being the literal maps of structures, create the pragmatic framework for a complex narrative of built space - they map the site and are the means by which we are able to experience the space of the constructed landscape. Historic architectural drawings and plans are anything but static documents; rather they represent an intricate historical narrative revealing the aspirations of society and the collective imagination of the culture. The structures always represent the view society has of itself, and how it presents its accomplishments to the world. The structures represent the culture's prideful perceptions of self, individual and collective - ranging from the prosaic to the sublime. P Drawn into the spaces of architecture by the experience of growing up in the house my grandfather, Thomas Leslie Rose, designed, it was not until my father, also and architect, gave me a copy of my grandfather's memoir that I became aware of his remarkable history. Using this memoir, written between 1932-3 - just a few years before his death in 1935 - as a script, I am linking my interest in the phenomenology of place with the histories of his projects. This primary text narrates his introduction into architecture through his apprenticeship with J.J. Egan in Chicago and continues to his meeting and partnership with Charles Kirchhoff in Milwaukee. I have taken the liberty of editing the text to those sections that relate specifically to his training and practice. P This project is the creation of a fiction based on the historic architectural plans and drawings of Thomas Leslie Rose and his partner Charles Kirchhoff and should not be considered as a documentation of particular work by the firm. My observations and interpretations of the existing structures as a visual artist are represented in the photographed and edited images of the structures. The photographed drawings are engaged but not paired with the photographed images. It is the intersection between the fact of the map and the experience of the map that interests me. My images are an attempt to provide one view of the work of Thomas Leslie Rose through the frame of time - the distance from what the structures were in their own time to my reading now made possible by their continued presence. This work is about my readings of these built places - the fictions and narrative I have read into the lived spaces.

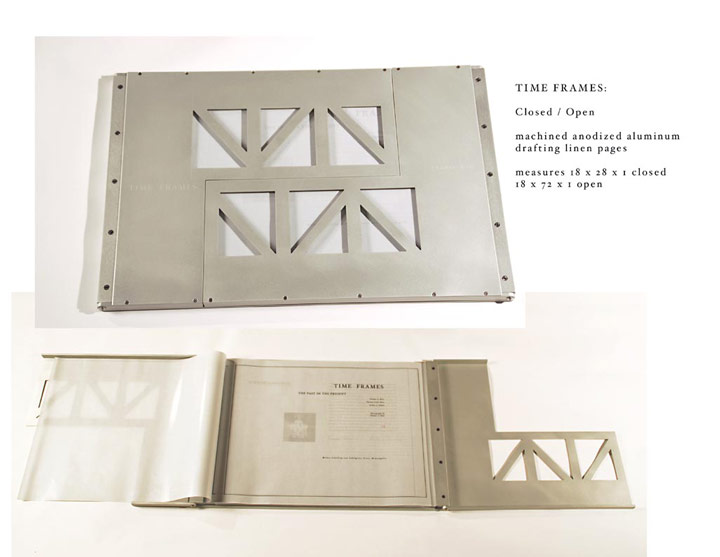

Time Frames

Time Frames is a limited edition, hand made book capturing the phenomenological experience of architectural space distilled into images. Arthur C. Danto writes the Introduction, "The Past in the Present". The project has its origin in my grandfather's memoir, written in 1932-33 and has been edited by me to the sections describing his apprenticeship with the architect J.J. Egan and his evolution as a practicing architect.

My objective is exploring the beauty, romanticism and mystery imbedded in his drawings and revealed in the structures, to exhibit that mystery and to open a dialogue on architecture as the embodiment of time. I have taken liberties by photographing the drawings in fragments, excerpting sections and using them to explore aesthetic aspects of style and media that lie outside his intentions. The spaces are photographed and the photographs are then subtly altered to suggest an ambiguous narrative of place. I have respected the original work and I have tried to explore its beauty and mystery.

Four buildings designed by my Grandfather Thomas Leslie Rose and his partner Charles Kirchhoff between 1900 and 1926, constitute the body of the book; they are, the Orpheum Theater in Minneapolis, the Palace Theater in New York, the Herman Uihlein residence in Milwaukee, and the Second Ward Savings Bank in Milwaukee. I have taken photographs of a selection of fragments from original drawings in the Milwaukee public library architectural archive and of the actual spaces as they currently exist to create a document of my experience with these places and with their histories. It is a document of time that frames the past in the present.

- Size: closed 19x28x1 and 19x68x1 opened.

- Cover: machined aluminum clear anodized.

- Text: 25 pages of text, foreword, the introduction and the edited memoir.

- Images: 77 photographs of the interiors and exteriors of four buildings and their drawings - plan, elevation and section.

- Pages: 102 pages printed on old drafting linen similar to that used at the time of the original work on the projects.

Foreword

1470

The Past in the Present

Arthur C. Danto

There are two modes of what, with a certain ontological bravura, I shall designate "historical being," which, taken together, set us off as a species. Both modes, from early on, have engaged me as a philosopher, since each involves a peculiarity of knowledge as well as of language.

The first mode can be made salient by considering what I call "narrative sentences". An historian says "Erasmus was Europe's greatest pre-Kantian moral philosopher," without anyone thinking twice. But no one could have said "Erasmus is Europe's greatest pre-Kantian moral theorist," for the obvious reason that the speaker — a contemporary of Erasmus — would have died well before Kant was born, let alone written Foundations of a Metaphysic of Morals. "Petrarch opened the Renaissance," is made true by events in Petrarch's future that neither he, nor his contemporaries, could have imagined.

The other mode of historical being is not quite so readily indexed to matters of tense, reference and observation, but it is of no less human importance than viewing life as narratively structured. It concerns the fact that we are always living in a historical period. A period — or a culture — is the weave of everything in what Hegel called its "objective spirit," consisting of all the institutions of human life at a given time — language, art, clothing, laws, etc. In any period, there are certain temporal concepts indispensable to the conduct of life. Earlier and later; before, after, and at the same time; now and then. But these do not enable those who belong to a period to experience time, as most of us do, historically — seeing things as belonging to other periods. Hence people can not experience their own period as a period.

In the present work, Thomas Rose is interested in how we experience time historically. In my view, his concern is with how one period leaves traces of itself in later periods to which those traces do not belong historically.

Subhead

Rose's grandfather, Thomas Leslie Rose, designed many buildings in his era, but my interest here lies in what must have been his masterpiece — the Palace Theater in New York. The Palace went up in a period that it reflects — the so-called "Progressive Era" of American politics, from the 1890s to the 1920s. Its essential structure still reflects that period, when it was America's premier vaudeville house, and "playing the Palace" was the ultimate accolade of variety artists.

Today parts of the Palace Theater belong to the period in which it was built, and do not belong in our present architectural period, other than as residues. No one today would or perhaps could erect an interior with the Palace's decorative details, except as a replica, a facsimile — a re-production. Such a work would have an entirely different spirit from the surviving theater; it would belong to our period entirely, whereas what remains of the Palace is present in our period without belonging to it. Straddling two periods, we experience the theater in the light of our period, and hence we experience it historically.

Let me introduce a piece of philosophical structure. In his masterpiece Being and Time, Martin Heidegger wrote of a Zeugganz — a whole consisting of different tools that "refer" to one another: the hammer refers to the nail, the nail to the plank, the plank to the saw, the saw to the carpenter's square. It is as if the system of tools came into being as a whole. One could not just have the saw; there have to be things to cut — namely, planks — for the saw to make sense. And the planks have to be connected if something is to be built, so we have to have nails or something like nails. I would like to propose that a period is a whole in which the parts reflect one another.

The period to which the Palace belonged reflected the kinds of acts it was built to show to people who had the leisure to be entertained and enough disposable cash to pay for them. Vaudeville was a going practice in the year the theater was built, 1913, and its builder, Martin Beck, specifically intended to bring the top acts to New York. There was obviously already a hierarchy of acts and certain "star turns" that people wanted to see, and the name of the theater, "The Palace," connoted an entertainment elite for an audience that appreciated quality.

But interest in vaudeville ended abruptly. The Palace became a place to show and see movies in November 1932, and both the name and the Neoclassical architectural style became irrelevances — residues of a vanished form of life. To experience them now with reference to the period to which they belonged is to experience time historically. Tom Rose's images of his grandfather's architectural achievement are presented here as a way of enabling us — his viewers — to have that experience.

Subhead

An important aspect of the design of the Palace Theater was its beautiful integration into the building that housed it. An extruded arch, implying the proscenium arch, was set into the rusticated exterior facade, just over the marquee. This was crowned by an escutcheon, framed by swags on either side. A rhythm of swags then crossed the entryway, just above the marquee; and the facade itself was punctuated by baronial ornaments symmetrically positioned relative to the entryway. In like, but inverted, manner, the interior of the theater was marked by an outside balcony, surmounted by lamps and a row of three windows, divided from one another by frames enlivened by cartouches.

This decorative program was restrained but insistent. It was palatial, as the name required, intended to architecturally assure visiting throngs of their privilege at entering so noble a space. Specifically, the arch proclaimed a welcome that framed the imagination of ticket-holders, who would have been directed by doormen/ticket-takers in swagged livery through the inner portal to ushers who would have escorted them to their seats. The facade was a promise of the artistic excitement that waited within. The Palace was a palace, a fairy site of magic displacement. It belonged to its time and place by the way it identified itself as not of its time or place. It was elsewhere made present, a fantasy the architecture helped imprint on the imagination of theatergoers. Tom Rose's work is composed, in addition to his grandfather's memoir, of the latter's drawings for the Palace and for other of his buildings, and of photographs the grandson took of some of these buildings, and especially of the interior of the Palace Theater. It has in consequence something of an archeological excavation, with strata belonging to different periods.

The memoir, though written in the 1930s, is in a style that belongs to the earliest stratum. There is not a line in it that could spontaneously have been written today. It presents the tone of a self—made man, a Horatio Alger who remembers hard times, which he faced with a nineteenth-century fortitude, and it evinces a philosophy of craftsmanship that goes back even further.

The beautiful architectural drawings, together with the neat lettering — reproduced on architectural cloth! — would already have looked old fashioned when World War I ended and the twenties arrived. Their program of ornamentation belongs to the first generation of multiunit dwellings that went up in New York in the 1910s — when there was a demand for the highrise buildings that become emblematic of New York before the era of the skyscraper, and when electric motors could only lift elevators eleven or twelve floors.

In the theater, the cartouches and the escutcheons, the bead-and-reel moldings, the fruited swags, the shallow domes, the pillars and balustrades — and the proscenium arch itself — all came from the vocabulary of the eighteenth-century Adams style, adapted from the Rococo, and were probably found in architects' manuals of the late nineteenth century.

p. 3 | close(X)

The photographs are twenty-first century, of course, intended to convey a feeling of pastness, and they testify to the phenomenology of experiencing time historically. But, as I said, there is more to experiencing this work than that. Those who sat in the theater in its moment of glory did not experience it historically at all. They thrilled to a sense of glamour, to the production of which everything in the architecture and on the stage aspired.

Tom Rose's work gives us another kind of experience altogether. I have sought to articulate its philosophy and something of its psychology. In its own way, the experience is much the same as that one might have had visiting the ruins of ancient Rome in the eighteenth century. In addition to time, it evokes a pathos of beauty and melancholy.